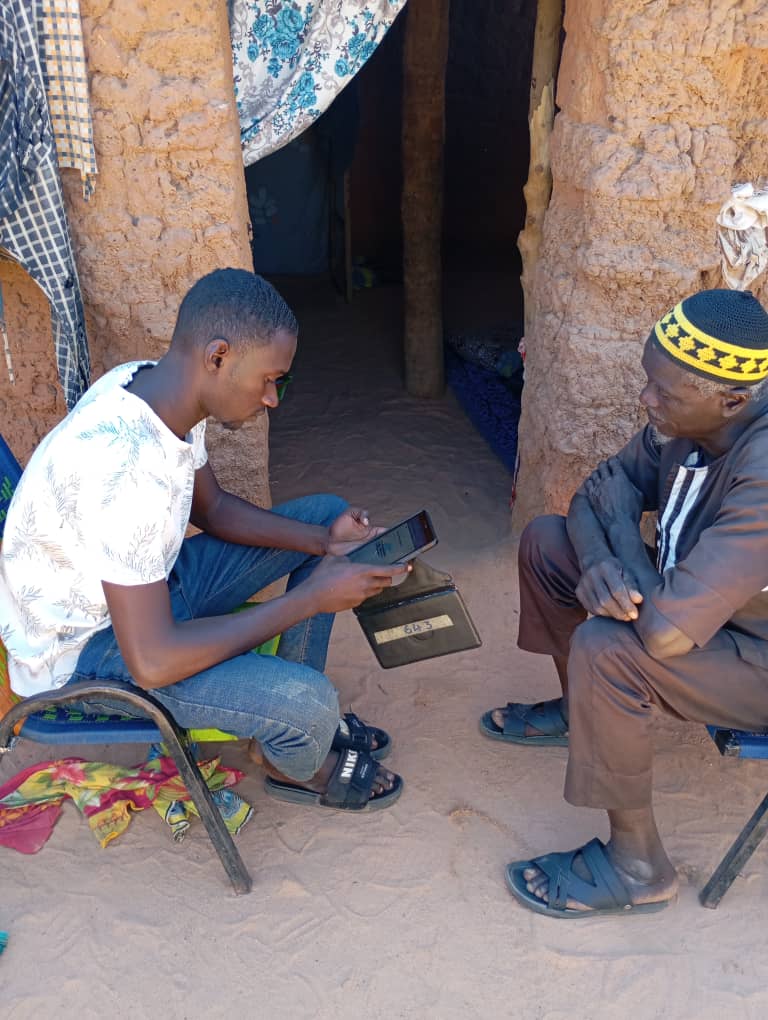

Farmers in their field, taken during the baseline socioeconomic survey in Tillaberi, Niger, in 2024 by Arnaud Dakpogan

Roots that run deep

Across Niger’s drylands, farmers have long shown that trees can come back from the roots. Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR) is the practice of selecting shoots from living stumps, pruning them well, and protecting them so they mature among crops. The approach is simple and low-cost, yet it can transform fields: shading crops, improving soil, and providing fuelwood and fodder in the long dry season. A new study from GeoField community members asks if farmers receive both practical FMNR training and support to formally document their land, will more of them adopt the practice, and will farms perform better over time?

A team of researchers from J-PAL, AidData, CIFOR-ICRAF, World Vision, and partners in Niger designed a randomized controlled trial that blends field ecology, household surveys, and satellite data to generate answers useful for policy and practice. Jessica Wells, a research scientist at AidData, and Arnaud Dakpogan, a J-PAL research fellow working on the Niger evaluation, are some of the key members of the team and were interviewed for the purposes of this blog.

“We are measuring the impact of FMNR itself and whether providing land rights boosts FMNR uptake.”

— Jessica Wells, AidData

Why FMNR matters now

Planting saplings has a mixed record in the Sahel. Survival rates are often low and costs high. FMNR builds from what is already underground, regenerating native species adapted to local conditions. Farmers who adopt gain shade, better microclimates, and healthier soils. As researcher Arnaud Dakpogan explained, its appeal lies in the fact that it starts with resources already on the farm.

“FMNR appeals to farmers because the roots already exist in the field. You do not need to buy seedlings. Since the decree, farmers can grow trees and use the fruit, leaves, and twigs from their own fields.”

— Arnaud Dakpogan, J-PAL

People are more likely to invest in trees when they feel secure in their ability to benefit from them. In 2020, Niger issued a decree that clarified how farmers can manage and use trees on their fields, removing a longstanding disincentive created by older forestry rules. The study examines whether this clearer policy environment, paired with practical legal support, makes FMNR more attractive and more sustainable. Documented rights could shift who participates in decision-making, how families invest in their plots, and how much time women and children spend collecting firewood.

How the study is designed

The evaluation spans three municipalities in Niger: Kourteye, Karma, and Koure, all located in the region of Tillabéry. Roughly three thousand farmers are randomly assigned to one of three groups: FMNR training only, FMNR training plus legal assistance to obtain customary land certificates, and a comparison group with no intervention. Training is the common entry point, allowing the team to test whether clearer rights amplify adoption and benefits beyond training alone.

Baseline work began in 2024, with follow-up rounds planned through 2027.

What success would look like by 2027?

CIFOR-ICRAF applies the Land Degradation Surveillance Framework (LDSF) with a mobile workflow to track woody vegetation structure, soil condition, and erosion at fixed plots. AidData integrates Earth observation to estimate tree cover change and patterns of degradation, validating satellite signals against LDSF plots and parcel GPS points.

Household surveys capture land use, conflicts, investment and credit, yields and revenues, food security, and household labor, with a focus on fuelwood collection.

“We’re capturing parcel GPS boundaries and pairing them with satellite imagery so we can identify what’s growing and track changes between survey rounds.”

— Jessica Wells

The team expects to learn when and where FMNR delivers measurable gains and what factors help it scale. Early success means farmers applying core practices within the first two seasons, selecting shoots, pruning at the right times, spacing trees so crops thrive, and protecting stems from grazing.

Longer-term indicators include:

Why Earth observation matters

Satellite data allows the study to monitor the same fields across seasons and years, even where field teams cannot visit regularly. By linking parcel maps and household surveys to remotely sensed data, analysts can track subtle changes that may only become clear over time. That persistence is especially important in semi-arid systems where one rainy season can disguise deeper trends.

The audience extends well beyond researchers. Ministries and local land commissions can use results to guide extension services and support for certificates, including ways to make documentation more accessible to women. NGOs can design the right mix of training, follow-up, and legal assistance to sustain adoption. Regional initiatives like the Great Green Wall can align restoration targets with practices farmers are willing and able to maintain.

This post does not present findings, as the study is still ongoing. The full picture will come into focus at endline. In the meantime, we’re sharing why researchers chose to pair FMNR with documented rights, how the study is designed, and what early signals to watch as data begin to roll in.

What comes next

Training, legal support, and follow-ups continue through 2027. Mid-study insights will be shared with local partners and the GeoField community of practice. Full results will inform national guidance on FMNR, and tree use rights.

If your organization is considering FMNR or rights-based initiatives and wants to align program design with measurable outcomes, connect with GeoField and join the community of practice to compare methods and share lessons. GeoField’s role is to connect evaluators, implementers, and Earth-observation experts so programs are designed with measurement in mind and evidence moves quickly into policy and practice.

Acknowledgments

Research team members include Arnaud Dakpogan, Nathan Fiala, Leigh Anne Winowiecki, Jules Bayala, Karl Hughes, Ibrahim Ouattara, Ariel BenYishay, Jessica Wells, and Hamed Constatin Tchibozo. Fieldwork is led by IREG with Nigerien partners. Related efforts like Regreening Africa implemented by CIFOR-ICRAF have reached tens of thousands of farmers in Niger, providing context for scale but separate from this trial.